Now Reading: What is the General Will? A Simple Guide to a Big Idea

-

01

What is the General Will? A Simple Guide to a Big Idea

What is the General Will? A Simple Guide to a Big Idea

Have you ever wondered how a group of people decides what is best for everyone? It’s a tricky question. We all have our own wants and needs. Maybe you want pizza for lunch, but your friend wants tacos. If there are only two of you, you can compromise. But what happens when you have a whole country full of people? This is where a fascinating concept called the general will comes into play. It sounds a bit fancy, but it is actually an idea that helps explain how democracies work.

In this article, we are going to explore this big idea in a way that is easy to understand. We will look at where it came from, what it actually means, and why it is still important today. We will break down complex philosophy into bite-sized pieces so you can see how the general will affects your life, even if you didn’t know it existed.

Key Takeaways

- The general will is a political concept made famous by Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

- It represents the collective interest of the people, rather than individual selfish desires.

- This idea is a foundational block for modern democracy and voting systems.

- Understanding the difference between “will of all” and “general will” is crucial.

- The concept faces criticism because it can sometimes be used to justify strict government control.

The Origins of the General Will

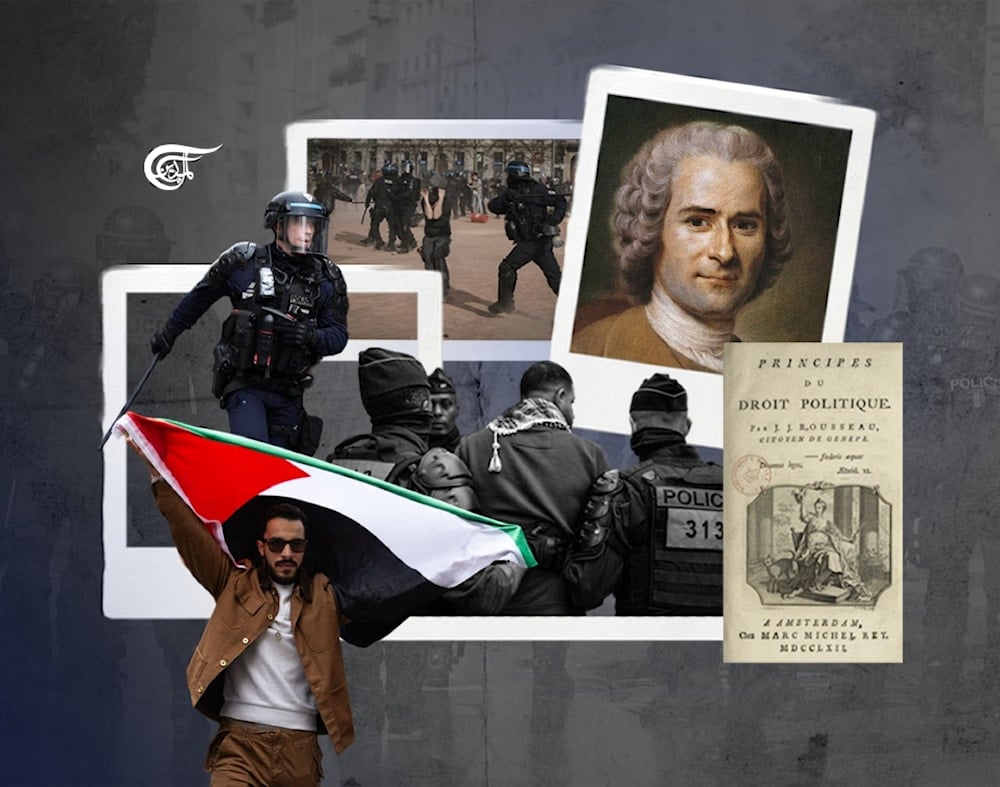

To really get what the general will is, we have to hop into a time machine. We need to go back to the 18th century, a time known as the Enlightenment. This was a period when people started questioning kings and queens and thinking about freedom. The superstar of this concept was a man named Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He wasn’t the first person to use the phrase, but he is definitely the one who made it famous. Before him, thinkers like Montesquieu and Diderot touched on similar ideas, but Rousseau really dug deep.

Rousseau wrote a very famous book called The Social Contract in 1762. In this book, he argued that people could only be truly free if they lived under laws that they created themselves. He believed that when we come together as a society, we make a deal with each other. We give up some of our individual freedom to gain the safety and cooperation of living in a group. The general will is the guiding force of that group. It is the voice of the people acting for the common good.

Who Was Jean-Jacques Rousseau?

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a philosopher, writer, and composer born in Geneva. He was a bit of a rebel in his time. While other thinkers were praising science and progress, Rousseau was worried that society was actually making people less happy and less free. He believed that humans were naturally good but were corrupted by civilization. His idea of the general will was his solution to this problem. He wanted to find a way for people to live together in a society without losing their freedom.

Rousseau’s life was full of drama and conflict, but his ideas changed the world. His thoughts on education, politics, and nature influenced the French Revolution and the way we think about government today. Even though he lived hundreds of years ago, his questions about how to balance personal freedom with the needs of the community are still super relevant.

Defining the General Will Simply

So, what is the definition? Imagine a sports team. Every player wants to shine and score points for their own stats. That is their individual will. However, the team also has a goal: to win the championship. To win, players might have to pass the ball instead of shooting, or play defense instead of offense. That collective goal—winning the game for everyone—is like the general will. It is what the group wants when they are thinking about the success of the whole group, not just themselves.

Rousseau explained that the general will is always right and tends to the public advantage. But he didn’t mean that people never make mistakes. He meant that the goal of the general will is always the common good. It is distinct from private interest. If you make a law that only helps rich people, that is not the general will. That is a particular will. The true general will applies to everyone equally and comes from all of us.

Individual Will vs. General Will

It is very easy to confuse what you want with what is best for everyone. Let’s look at a quick comparison to make it clearer.

|

Feature |

Individual Will |

General Will |

|---|---|---|

|

Focus |

Personal gain and private desires |

Common good and public interest |

|

Scope |

Affects one person or a small group |

Affects the entire community equally |

|

Motivation |

Selfishness or personal preference |

Fairness and equality |

|

Outcome |

Benefits the individual |

Benefits the society as a whole |

Understanding this difference is key. The general will asks us to put on a different pair of glasses. Instead of looking at the world through “Me” glasses, we look through “Us” glasses.

The “Will of All” vs. The General Will

This is where things get a little tricky, so stay with me. Rousseau made a very specific distinction between the general will and the “will of all.” You might think they are the same thing, but they are not. The “will of all” is just a sum of everyone’s private interests. It is like adding up everyone’s selfish desires and seeing what the total is. It is often a chaotic mix of conflicting wants.

For example, imagine a town vote on taxes.

- Will of All: Everyone votes to pay zero taxes because they want to keep their own money.

- General Will: The town realizes they need roads and schools, so the general will would be to pay a fair tax to support these shared needs.

The general will looks at what we have in common. It strips away the parts where we disagree because of our selfishness and leaves the part where we agree because of our shared needs. Rousseau believed that if you take away the “pluses and minuses” of our private desires, what is left is the general will.

How Does the General Will Work in Politics?

In a political system, the general will is the source of all laws. For a law to be legitimate, it must reflect the general will. This means that when a government passes a law, it shouldn’t just be because a powerful king or a rich lobbyist wants it. It should be because it is good for the citizens as a collective body. This is the heart of the idea of popular sovereignty—that the power to rule comes from the people.

When we vote in elections, we are technically trying to discover the general will. In a perfect world, when you go to vote, you shouldn’t just vote for the candidate who will give you a tax break. You should vote for the candidate who will do the best job for the country. Of course, in the real world, people often vote based on their own private interests. This makes finding the true general will difficult.

The Role of the Legislator

Rousseau knew that figuring out the general will is hard for a large group of people. Sometimes, the public wants the good but doesn’t see how to get it. This is why he introduced the idea of a “Lawgiver” or Legislator. This isn’t a king or a ruler. It is a wise person or group that helps draft the laws to guide the people. They don’t have power over the people; they just help shape the system so the general will can emerge.

Think of the Legislator like a coach. The coach doesn’t play the game. The team (the people) plays the game. But the coach designs the plays (the laws) that help the team work together to win. The coach helps the team realize its potential. In modern terms, our founding fathers who wrote the Constitution acted a bit like these Legislators. They set up the framework so that the general will could guide the nation.

Why is the General Will Important for Democracy?

Democracy is based on the idea that the people rule. But “the people” is a messy concept. We are millions of individuals with different lives. The general will provides the glue that holds democracy together. It gives us a moral compass. It tells us that freedom isn’t just doing whatever you want; it is living by laws that you helped create. This is what Rousseau called “civil liberty.”

Without the concept of the general will, democracy could turn into “mob rule.” Mob rule is when the majority simply bullies the minority. But the general will implies equality. Since the laws must apply to everyone equally, the majority cannot pass laws that hurt the minority without hurting themselves too. It forces a sense of fairness into the system.

Freedom and Obedience

There is a famous and controversial quote from Rousseau. He said that if someone refuses to obey the general will, they effectively “must be forced to be free.” That sounds scary, right? How can you be forced to be free?

Rousseau meant that true freedom is living by the rules you set for yourself as a society. If you break those rules (like stealing or hurting someone), you are acting on your lower, selfish instincts, not your higher, rational self. By stopping you from breaking the law, society is helping you stick to the agreement you made. They are forcing you to live by the freedom of the citizen, rather than the freedom of the animal. It is a debate that political scientists still argue about today!

Common Misconceptions about the General Will

People get confused about this idea all the time. Let’s clear up a few common myths.

- Myth: It means everyone has to agree on everything.

-

- Fact: No, unanimity isn’t required. While it would be nice, it’s impossible. The general will can be found through majority voting, provided people are thinking about the common good.

- Myth: It is the same as the majority opinion.

-

- Fact: Not always. A majority can be wrong! If 51% of people vote to take all the money from the other 49% just for fun, that is the “will of all” (or a part of it), not the general will, because it isn’t for the common good.

- Myth: It destroys individuality.

-

- Fact: Rousseau believed it protected true individuality by ensuring a safe, free society where you aren’t oppressed by others.

The General Will in Today’s World

You might think this is all old history, but look around you. Every time there is a debate about climate change, healthcare, or education, we are debating the general will.

- Climate Change: My individual will might want to drive a big gas-guzzling car because it’s fun. But the general will recognizes that we need clean air to survive, so we pass emissions laws.

- Public Schools: You might not have kids, so your individual will says “don’t tax me for schools.” But the general will understands that an educated society is safer and more prosperous for everyone.

We see this tension every day. When we debate laws, we are essentially arguing about what truly represents the interest of the community.

Applying the Concept

If you are interested in learning more about how big societal decisions are made, or perhaps you are looking for insights on global economics and leadership, you can find interesting perspectives on sites like https://forbesplanet.co.uk/, which covers a variety of business and lifestyle topics. Understanding the general will helps you analyze news and politics with a sharper eye. You start asking, “Is this politician appealing to our selfishness, or to our common good?”

Criticisms of the General Will

Not everyone loves this idea. Throughout history, some people have pointed out dangers in Rousseau’s thinking.

The Danger of Dictatorship

Critics argue that the general will is too vague. Who gets to decide what the “common good” is? In the wrong hands, a dictator could say, “I know what the general will is better than you do!” They could use it to silence opposition. Leaders like Robespierre during the French Revolution used Rousseau’s ideas to justify terror, claiming they were acting for the people. This is the dark side of the concept. If you say the people’s will is always right, it becomes hard to argue against the government that claims to represent it.

The Problem of Minorities

Another criticism is about minority groups. If the general will is supposed to be what is best for the whole, what happens if the majority ignores the specific needs of a minority group? While Rousseau argued the laws must be general, in practice, majorities often overlook the struggles of smaller groups. Critics say the theory doesn’t protect minority rights well enough.

Rousseau vs. Other Philosophers

It helps to compare Rousseau to other big thinkers to see where he fits in.

Rousseau vs. Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes was very pessimistic. He thought people were naturally selfish and violent. He believed we needed a strong King (a Leviathan) to control us. Rousseau disagreed. He thought people were naturally good and could rule themselves through the general will. Hobbes wanted order through fear; Rousseau wanted order through cooperation.

Rousseau vs. Locke

John Locke is the father of Liberalism. He focused heavily on individual rights—life, liberty, and property. Locke believed the government exists to protect these individual rights. Rousseau focused more on the community. While Locke worried about the government taking your stuff, Rousseau worried about the community losing its shared power. Both influenced American democracy, but they emphasized different things.

Key Terms to Remember

When studying this topic, you will run into these words often. Here is a quick cheat sheet.

- Sovereignty: The absolute authority to rule. Rousseau believed this belongs to the people.

- Social Contract: The imaginary agreement we make to form a society.

- Civil Liberty: The freedom we get by following laws we help create.

- Common Good: What benefits everyone in the society.

- Direct Democracy: A system where people vote on laws directly, which Rousseau preferred over representative democracy.

Can the General Will Exist in Large Countries?

Rousseau loved small city-states like Geneva. He thought the general will was easiest to find in small communities where everyone knew each other. In a massive country like the United States with over 330 million people, it is much harder. We have so many different cultures, religions, and economic backgrounds.

In large countries, we use representative democracy. We elect people to go to Washington or our state capital to figure out the general will for us. Does it work perfectly? No. But it is the system we have adapted to try and apply these ideas on a huge scale. The challenge for modern nations is keeping that sense of shared purpose when we are all so different.

Conclusion: Why It Matters to You

The general will isn’t just a dusty idea in a textbook. It is the reason you stop at a red light even when no one is looking. It is the reason we pay taxes to build libraries we might never visit. It is the invisible agreement that makes civilization possible.

Understanding the general will helps us become better citizens. It reminds us that while our personal wants are important, we are also part of something bigger. It challenges us to think about our neighbors and our country when we make decisions. Next time you see a debate on the news, ask yourself: Are they fighting for their own slice of the pie, or are they trying to make the whole pie bigger for everyone? That is the question Rousseau wanted us to ask.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the simple definition of the general will?

The general will is the collective desire of a group of people that aims for the common good or the welfare of the whole society, rather than the selfish desires of individuals.

Who came up with the concept of the general will?

While the term was used by others before him, the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau is the one who made it famous and fully developed the concept in his book The Social Contract (1762).

Is the general will the same as the majority vote?

No. A majority vote is just a count of numbers. If the majority votes for something selfish or harmful to the community, it is not the general will. The general will must aim for the common good.

Why is the general will important for democracy?

It provides the moral foundation for democracy. It explains why citizens should obey laws—because those laws represent their own collective will and interest. It legitimizes the power of the people.

What is the difference between “general will” and “will of all”?

The “will of all” is just the sum of everyone’s private, selfish interests added together. The general will is what remains when you subtract the conflicting self-interests and focus on the common interest that unites everyone.

Can the general will be wrong?

According to Rousseau, the general will is always “right” in the sense that it always aims for the public good. However, the people can be deceived or mistaken about what actually is good for them. So, the people can make mistakes, but the concept of the general will itself is defined as the ideal common good.